It’s bedtime. You lock the front door, check the windows, and go to bed. Then, in the middle of the night, you realise you’ve left the back door unlocked. You jump out of bed, race downstairs, only to find your house has been robbed.

This analogy (overly dramatic) is not unlike the dire COVID-19 situation unfolding in Papua New Guinea. Initially, PNG seemed to be managing the pandemic well. Like many other nations in the Pacific (including Australia and New Zealand) the air borders were strengthened. However, PNG is not like most Pacific nations in that it shares its main island with Indonesia, with the land border between the two nations remaining largely unprotected. It was a back door, and when cases arrived in the Indonesian province of West Papua, the virus literally walked across the border. It was only a matter of time before it strolled, unchecked, into Port Moresby. The porous nature of the land border was a critical oversight. Better risk-based decision making would have recognised this and other weaknesses and responded before reaching a crisis point.

This is a key concept - you can only prevent disasters if you act before the disaster happens. This is what risk management is - identifying and reducing potential calamities before they eventuate, and it’s a key concept to grasp no matter what industry you’re in, and it may just be the best way to respond to COVID-19.

In the context of disasters, the risk of a negative outcome (such as damage to people or property), is assessed and mitigated by considering the likelihood of being exposed to a hazardous event and the potential impact or consequence of that exposure. This means managing what could happen, which can be distinctly different from what has happened. In this sense, resources expended on reducing a risk that never eventuates should not be viewed as a waste, but rather as a reasonable investment.

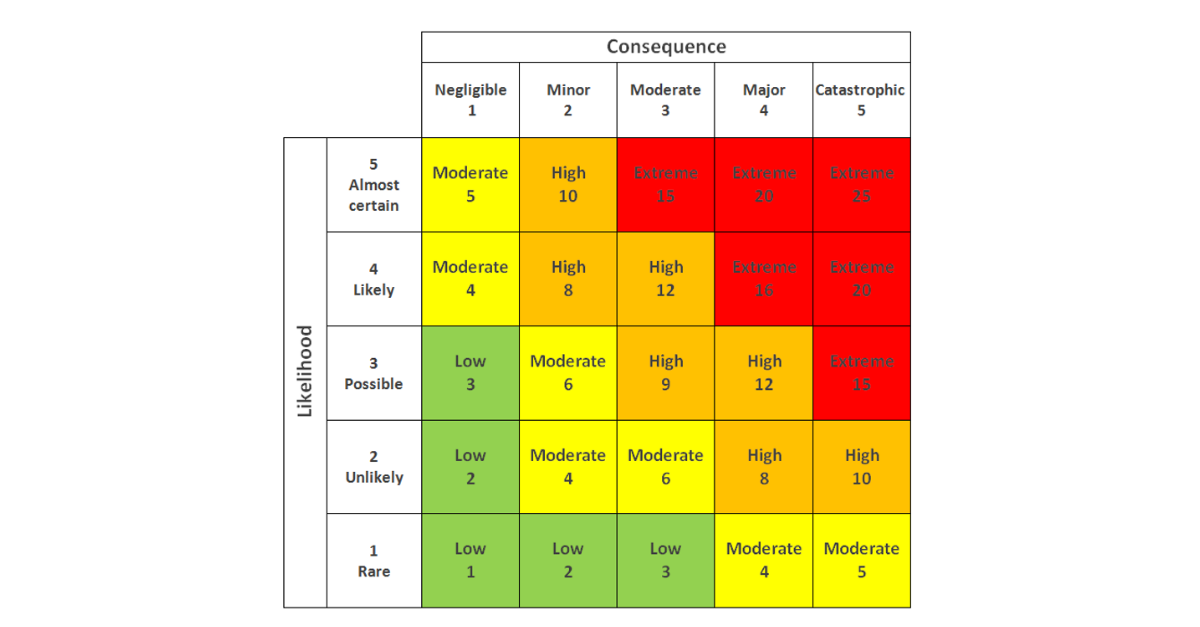

Quantifiably risk is a function of consequence and likelihood, below is generic risk matrix, the likes of which are used across many sectors. The riskiest scenario is one that is almost certain to happen with catastrophic consequences if it did and is assigned the maximum score of 25 and is coloured red. These types of risk matrices are used to estimate and compare levels of risk for different scenarios for many different types of risk (Health, economic, environmental).

Looking through this risk-based lens, the Australian COVID-19 story makes sense. The strict measures decision makers put in place minimised the likelihood of people’s exposure to the virus. These tried and tested measures have effectively reduced the likelihood of potentially disastrous public health and economic consequences for Australia to date. The current vaccination campaign, on the other hand, is aimed at reducing the health consequences if people are exposed to the virus (which can be deadly). Risk based decision making recognises that while Australia has so far performed well in containing the pandemic (by minimising the likelihood of community exposure) it wouldn’t take much to move us into the red zone. The likelihood of an outbreak remains elevated. In short, we remain at high risk from the pandemic.

Together with colleagues with international water and environmental public health expertise, I have recently developed a tool to help prioritise water related foreign aid in response to COVID-19. In this project, funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade through the Australian Water Partnership, we investigated the risk from COVID-19 in 45 countries in the Asia Pacific region and the role access to safe and sufficient water could play in reducing those risks.

This project used a risk-based framework which could evaluate how a country’s risk according to what phase of the pandemic they are in, whether they are trying to;

- Delay the virus arriving into their country

- Contain outbreaks by limiting community transmission

- Treat those that become ill, and

- Recover from the pandemic aftermath

This work has provided us with some interesting perspectives on risk-based decision making during the pandemic and beyond. From this work I have highlighted five principles of risk-based decision making, which are relevant no matter what industry you’re in. They’re also applicable to all risks, not just health and safety.

It is better to act early than late

Throughout the globe, countries that acted early by closing borders and slowing the virus coming into the country have generally performed much better. It is better if you can delay the virus arriving in a country, rather than attempting to contain its spread and wrangle the health ramifications of an out of control outbreak. This principle holds just as well in another context. For example, it is better for an organisation to have a strong review process for social media posts to prevent offensive content than having a strong policy for handling complaints.

Even if you have prevented disaster so far you may still be at risk

Throughout the Pacific, many countries brought in strict border controls and have so far prevented cases getting past quarantine. However, if Pacific Nations were to lift border restrictions and the virus did sneak out, most countries would struggle to contain it, leading to huge community transmission, and because of high comorbidities and limited access to health care in the region, there would be an exceptionally high mortality rate and loss of life. Closer to home, if no one has ever injured themselves at your office, it does not mean it cannot happen, this is the same for any type of incident.

If the disaster never comes, it does not necessarily mean the response was an overreaction

There are still pundits saying that the Australian government’s response was too burdensome on the economy despite Australia’s economy outperforming Europe and North America. The Victorian government, in particular, was criticised that their response was lacking, resulting in most of Australia’s cases, while at the same time receiving criticism for strict communist style repression from “Chairman Dan”. Each time a new restriction is announced to combat a new outbreak, the media is flooded with those saying it is too burdensome for the economy with seemingly little recognition that it is these very public health measures that have saved Australia from a situation like the US or Europe. The economic impacts are real, but the cost of inaction would have been far greater. This is an example of omission bias. A more familiar example would be insurance, just because your house never burns down, does not mean the insurance was not worthwhile.

Risks are dynamic, they evolve through time

It is vital that we understand how the risks associated with the pandemic evolve through time. Again, taking the Pacific as an example; countries must stop COVID-19 at the border. However, it’s a double-edged sword because while the health consequences are mitigated, there will be devastating economic and food security consequences from reduced tourism and trade.

For the work we have undertaken in the region, this meant we should recommend projects that help authorities identify the highest risk pressure points. In this case, we recommended containing the virus at the border by adding wastewater epidemiology at airports and border checkpoints alongside the other already strict quarantine controls. Also, as the pandemic progresses, there will be increasing pressure on Pacific governments to reopen for tourism and trade. Investing in agricultural water security to bolster the economy and food security may lessen some of this pressure.

Risk management must be applied consistently according to the risk, not the politics

As a final note about risk-based decision making, I would like to talk about the greatest challenge of this generation (yes even greater than COVID-19), climate change. Even if politicians entertain the “science isn’t settled” (which it is) argument, any reasonable opinion that is at all cognisant of scientific thought must agree that there is at the very least a high likelihood of catastrophic consequences. Like our government did for COVID-19, they must heed the advice of experts and bring in appropriate mitigation and adaptation measures, even if they cost us economically because the potential consequences of inaction are far greater. In the unlikely event that catastrophic impacts from climate change do not eventuate, this would not be wasted money, it would just be good risk management.

Dr Lachlan Guthrie is a Research Fellow and Project Manager (Integrated Water Management and WASH) at the International WaterCentre, Griffith University, Australia. Lachlan has extensive experience in integrated water strategic planning and water security and recently compiled a Water Security and COVID-19 risk index, ranking 45 countries in the Asia Pacific region according to their risk regarding COVID-19 and water security.

To visit Lachlan's Griffith Experts page click here

Professional Learning Hub

The above article is part of Griffith University’s Professional Learning Hub’s Thought Leadership series.

The Professional Learning Hub is Griffith University’s platform for professional learning and executive education. Our tailored professional learning focuses on the issues that are important to you and your team. Bringing together the expertise of Griffith University’s academics and research centres, our professional learning is designed to deliver creative solutions for the workplace of tomorrow. Whether you are looking for opportunities for yourself, or your team we have you covered.

Advance your career with Griffith Professional

Griffith's new range of stackable professional courses designed to quickly upskill you for the future economy.