Creating Pathways to Child Wellbeing and the Prevention of Crime is a long-term research and action program that was initiated in 1996 by Emeritus Professor Ross Homel, AO and which continues today.

The core Pathways research team comprises Ross Homel, Kate Freiberg, Sara Branch, Jacqueline Allen, and Tara McGee.

The overall aim of the program is to strengthen the development system for children, with a long-term view to improving the wellbeing of children, reducing youth crime, and broadly promoting both human and community development. The basic focus is policy pathways, since the project aims to reorganise government, as well as societal priorities and practices, and move tertiary, punitive responses to social problems (especially for youth crime and substance abuse) to primary prevention - the prevention of problems before they emerge or become entrenched.

The program has been funded by a wide variety of agencies including the John Barnes Foundation, The Australian Department of Social Services, and the Australian Research Council through Grant Numbers C0107593, LP0560771, DP0984675, DP140100921, LP130100142, and LP170100480.

Creating Pathways to Child Wellbeing and the Prevention of Crime comprises three major phases:

Phase 1 (1996-2001). Review and Plan

Inspired by publications by the late Professor David Farrington from Cambridge University, in 1996 Ross Homel posed the question: what is Australia doing in light of the growing evidence for the crime prevention effectiveness of early-in-life initiatives like the Perry Preschool Project? The answer at the time appeared to be “nothing much,” although early intervention – as opposed to early or primary prevention - was a well understood concept in areas such as mental health and disabilities research.

Ross set about securing funding and in 1997 was awarded a grant by the Commonwealth Department of the Attorney General to bring together and lead a multidisciplinary team of eminent Australian researchers (called the Developmental Crime Prevention Consortium) to document and review what developmental prevention and early intervention initiatives were being implemented at the time in Australia that could be related to the prevention of youth crime. A major objective was to describe in some detail the principles of development crime prevention and to make recommendations about what Australia could do to strengthen its social policies.

This work culminated in a report published in late 1999, Pathways to Prevention: Developmental and Early Intervention Approaches to Crime in Australia. This foundation report has had a major influence in Australia on policies in such diverse fields as mental health, substance abuse, child protection, and special education, but much less impact on state government policies and practices concerned with youth crime, where the primary prevention of youth crime is rarely a focus. The report did succeed in putting developmental prevention and early intervention onto the ‘social policy map’ in Australia in a manner that made them central, rather than peripheral, to policy debates in some fields such as youth mental health and drug policies, but the gap between rhetoric and the old realities in these fields remains very large. State government policies remain very largely focused on accountability and punishment rather than research-informed primary prevention and early intervention on youth crime.

A major recommendation of the 1999 report was that a community-based demonstration of developmental crime prevention should be designed and implemented. Ross accepted this challenge and in 2000 and 2001 undertook the task of attracting funding from philanthropic and state government sources and from the Australian Research Council. At the same time, he worked with colleagues to select a suitable disadvantaged community and begin an ongoing process of engagement, including paying local students and parents to design and implement a survey of the needs of children in the area.

Phase 2 (2002-2011). The Pathways to Prevention Project

The Pathways to Prevention Project aimed to be a demonstration of how developmental initiatives in disadvantaged communities could be designed based on the science of human development in a way that empowered both residents and mainstream institutions such as schools and NGOs to mobilise resources to promote positive child development for all local children.

In specific terms, the project was designed to address the gap in knowledge about how to make commonly used family support and place-based child services including preschool and school more effective in the short and long term, and more generally how to make the developmental system more responsive to the needs of disadvantaged children.

Influential in its early design was evidence emerging from longitudinal research pointing particularly to low achievement, poor parental child-rearing behaviour, child impulsivity, and poverty as critical risk factors that should be addressed through multimodal approaches involving children, schools, families and the community. In developmental system terms, these risk factors highlight the frequently fractured relations between schools and families in socially disadvantaged areas, and the corrosive effects of poverty and social exclusion on the capacity of parents and carers to parent effectively. Bluntly put, families are stressed, and children are damaged because the developmental system is broken.

The project operated in a highly disadvantaged area of Brisbane as a research-practice partnership involving families, seven local primary schools, the Griffith University research team, the Queensland Department of Education, and national community agency Mission Australia. The Pathways area had a youth crime rate in the late 1990s more than eight times higher than the Brisbane average.

The first phase of the project in 2002 and 2003 incorporated an enriched preschool program focused on oral language development and communication skills for all 4-year-old children attending two of the seven free state preschools in the area. The link between poor oral language skills and difficult behaviour was a problem highlighted by all preschool teachers when they were asked in 2001 by a small team of residents and students trained by the research team to find out about the most pressing needs of children in the area. The Communication Program was fully integrated with the normal preschool curriculum and was developed and implemented by specialist Education Department teachers who worked closely with classroom teachers and the parents of the children. The aim was to integrate as tightly as possible the preschool classroom environment with the home environment, so that activities in each setting would be mutually reinforcing.

The Mission Australia team invested much in the building of trust through community relationships and constructed and evaluated a holistic suite of program activities that were available to all families on a completely voluntary basis, including many participating in the Communication Program. These activities, which were often situated in schools and involved teachers, were based on community-generated data on needs, maximized engagement with the most hard to reach families, employed a mixture of professional staff and community workers without formal qualifications who had a high degree of credibility with their ethnic communities (First Peoples, Pacific Islands or Vietnamese), and were tailored to the needs of each child or family by being strength-based and highly flexible in terms of type of service, duration, and intensity. Decisions about what programs to implement and the manner of implementation were not generally made by researchers but by the Mission Australia Service Manager and by teachers and school principals, although usually after extended discussion with researchers about goals and the research evidence.

Thus, the project incorporated a range of program activities, from facilitated playgroups to intensive family support, that represented a broad cross-section of services typically found in socially disadvantaged communities in Australia. The programs were, however, perhaps more than usually ‘research influenced.’ The Pathways Project (or Service, as it was termed by the Mission Australia team) was very successful in reaching out to families, especially those with a high level of need. Between 25% and 30% of all families with children enrolled at one of the seven primary schools participated in the service in any given year, with a total of 1,077 distinct families participating between January 2002 and June 30, 2011.

1,467 children from these families (30% of all enrolled children) participated over the ten years (nearly always with a parent): 16% First Nations, 26% Vietnamese, 15% Pacific Islanders, 16% other ethnicities, and 27% ‘Anglo-Celtic’ Australian. The mean number of contacts per family was 61; the mean period of total involvement was 76 weeks; and on average 3.5 service types were accessed, most commonly carer individual support; advocacy; and playgroups. These high levels of involvement, often over many months or years, underline both the extent of need in the area and the success of the Pathways team in building trust and offering resources that families really valued.

A 2024 evaluation report summarises the improvements in classroom behaviour, parental efficacy and empowerment, and child wellbeing achieved during the life of the project and since 2011. It documents in detail how improved behaviour brought about through the Communication Program combined with family support led to a reduction of more than 50% in the onset of serious youth offending. This Pathways Project effect was reflected in a community-wide reduction of more than 20% in rates of youth crime in the years when the communication program participants were potentially at risk.

A further paper explores the cost-effectiveness of the Communication Program. Results show that for every dollar spent, the Communication Program generated an average return of AUD7.65 from avoided court-adjudicated youth offending. The Pathways to Prevention Project is the first Australian early-in-life crime prevention initiative to present scientifically persuasive evidence for effectiveness in reducing the probability of onset of serious youth offending, offering a counternarrative to prevailing expensive youth justice policies centred on child accountability and harsh punishments.

The Pathways Project shared first prize in the 2004 National Crime and Violence Prevention Awards. In April 2004, the Prime Minister John Howard announced a new multi-million-dollar program, Communities for Children, that was implemented in 52 disadvantaged communities across Australia. This program was strongly influenced by the learnings from Pathways to Prevention. On December 7, 2006, the Prime Minister launched a report on the first five years of the Pathways Project at Parliament House in Canberra.

In 2024 the Pathways team won a further National Crime and Violence Prevention Award for the impact of the project in reducing serious youth crime. The 2024 report documenting these outcomes was rated as the best publication of the year in the field of crime prevention, winning the 2024 Adam Sutton Crime Prevention Award administered by the Australian and New Zealand Society of Criminology.

Phase 3 (2012-2020). The CREATE Project: Creating Pathways to Child Wellbeing in Disadvantaged Communities

The research team embarked in 2012 on an 8-year research program that aimed to translate many of the findings and the methods developed in the Pathways to Prevention Project into existing government programs that funded partnerships in disadvantaged communities across Australia. Communities for Children (CfC), funded and administered through the Commonwealth Department of Social Services, was chosen as a suitable vehicle for the CREATE Project.

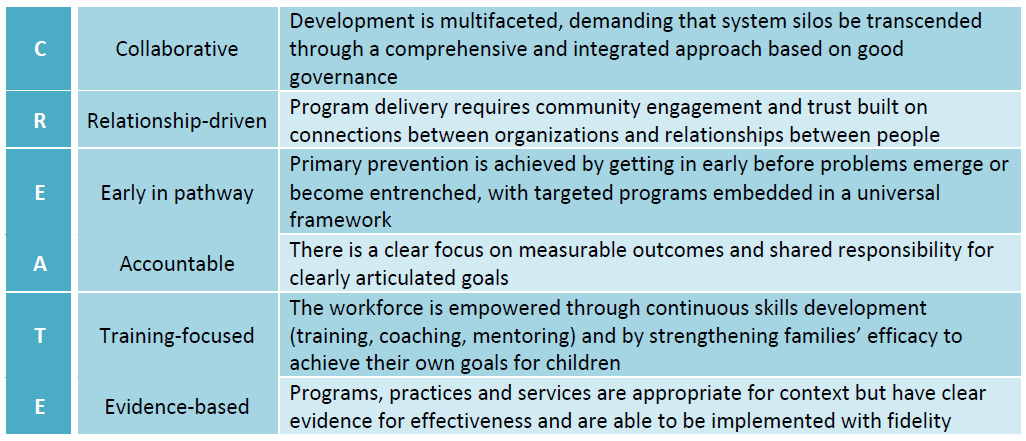

The CREATE model was developed toward the end of the Pathways to Prevention Project, in 2012. The model is a set of principles and an action methodology underpinned by good governance and community empowerment. CREATE is both an acronym and a framework that builds capacity for collective impact in communities by enhancing the ability of child-serving organisations to operate as part of an integrated system of care for children and families:

The goal of the CREATE Project was to build and implement a Prevention Translation and Support System (PTSS) progressively in Communities for Children (CfC) sites in NSW, Queensland and Tasmania, and to evaluate its impact on measures of child wellbeing, educational performance, and behaviour, as well as on family-school engagement and the quality of functioning of local partnerships involving schools and community agencies.

The PTSS incorporates a range of electronic tools and resources, and the services of Collective Change Facilitators (CCFs) in each community. The PTSS is a set of structured processes and resources that equip community partnerships (or coalitions) to achieve their aims. The PTSS blends face-to-face guidance, mentoring and coaching provided by CCFs with a comprehensive range of interactive on-line resources and training. A CCF helps bridge the gap between prevention science and routine community practices, guiding local partnerships as they move beyond the status quo toward the scientific practice of collective impact.

The PTSS resources were designed to support community coalitions as they moved through the fives phases of the CREATE Change Cycle:

Electronic tools and resources

Informative videos; and an extensive array of tools and resources to guide the coalitions through the CREATE change cycle;

A validated measure of child wellbeing: Rumble’s Quest, a 30-minute video game for 6-12 year-old children

The Parent Empowerment and Efficacy Measure (PEEM) on-line, called Parent’s Voice

A comprehensive on-line tool for measuring, reporting, and acting on the quality of functioning of CfC community partnerships (the Coalition Wellbeing Survey).

Publications from the Creating Pathways to Child Wellbeing and the Prevention of Crime Research and Action Program

These publications include papers reporting the theory, development, implementation, evaluation, and dissemination of the Pathways and CREATE Projects, as well as publications that develop the theory and research foundations of developmental prevention building (in part) on both projects (e.g., Homel, 2005). In addition, policy papers, commentaries and lectures related to the project are listed. Papers in preparation are not listed, nor are reports and commentaries that are no longer easily accessible, but we do include papers available in preprint or ‘under review’ format.

Contact Criminology Institute

Phone

Location

Macrossan Building (N16), Level 0

Postal address

School of Criminology and Criminal Justice

Griffith University

170 Kessels Road Nathan QLD 4111

Connect with us