Let's be honest, we've all been subjected to professional development that's been poorly planned with no clear learning outcomes. It doesn't have to be this way. Engaging in professional development is key to ongoing success and satisfaction in our professional lives. Keeping our skills up to date, being aware of new technologies and trends increase our employability. From an organisation’s perspective workplace development can give your business’s competitive edge a boost. Why then, is it often so hit and miss?

Undertaking a specific learning program to gain a new skill is only as good as the decision process by which the training was conceptualised. If we take a step back from the specific training, knowing what new skills or knowledge to acquire, and for what purpose, is a key skill in itself.

Whether for an individual or team, getting the design of learning right is critical. Creating a successful learning session or program involves knowing precisely what needs to be learned, and matching proven learning strategies to the outcomes. But if you’re thinking about your own PD, or the needs of a larger, more diverse team, how exactly do you undertake this step?

Of course, those with experience in developing people will understand the connections between learning needs and teaching or training methods. Leaders and experienced teachers or trainers will know what is likely to work and what won’t. Deep understanding of an organisation’s objectives and what has worked in the past no doubt plays a part. But whether you’re a seasoned pro in professional development or just starting to consider professional learning needs there are proven strategies, based upon years of research, to help you identify required skills and knowledge and how to select activities that will drive effective learning.

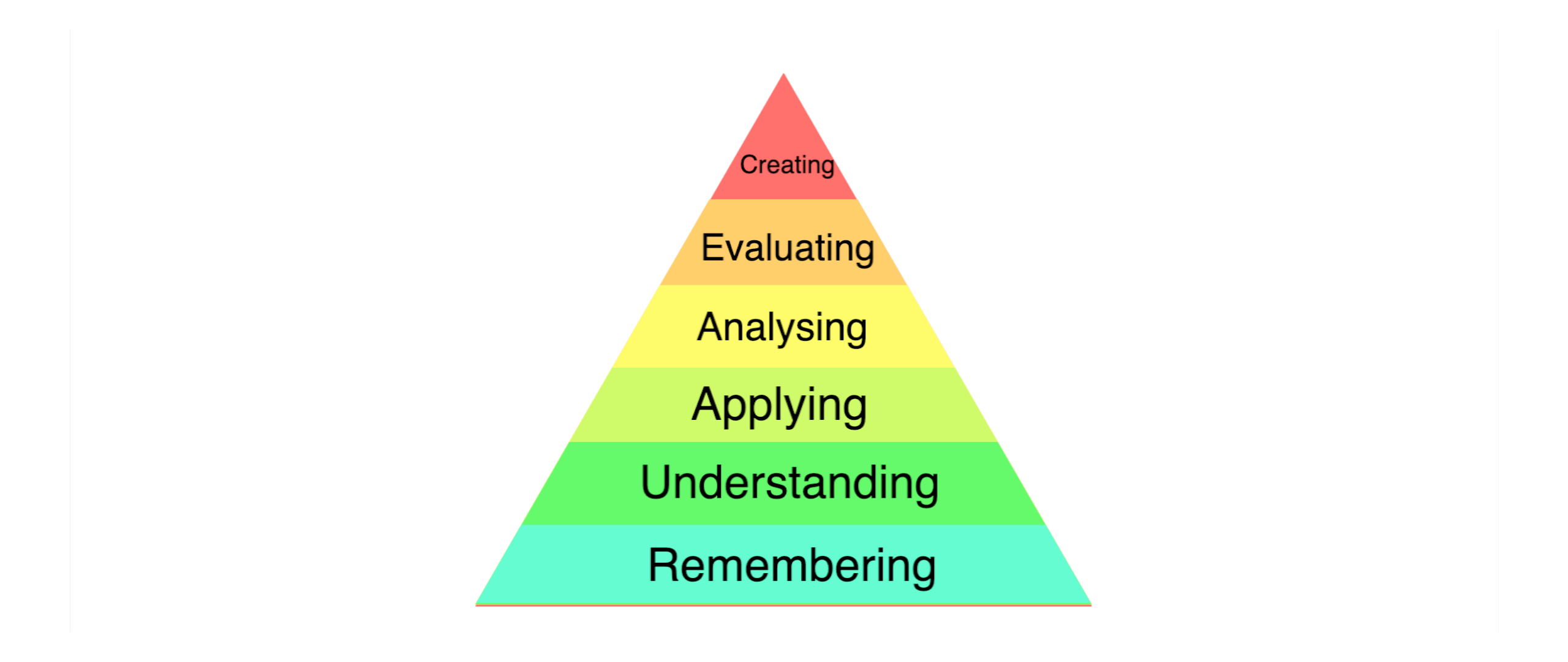

One way to start thinking about it is by using ‘taxonomies’ of learning. A taxonomy gives us a way of breaking down our ideas of what needs to be learned into precise segments. A notable example is the taxonomy developed by U.S. researcher Benjamin Bloom and colleagues in the 1950s. They wanted to create a reliable way to separate simple from more complex types of learning. Their taxonomy involved six levels – knowledge, comprehension, applying, analysing, synthesising and evaluating. The original Bloom taxonomy has been refined and expanded on over the years, and now looks something like the graphic below. Note the pyramid structure, with one layer providing the foundation for the layer that sits above it. Bloom’s original taxonomy had evaluating at the top, but creating now sits at the apex, signally the most complex of tasks – creating new ideas.

The beauty of a taxonomy like this is it helps us ask appropriate questions about what needs to be learned. Do we just want people to know something (like the steps of resuscitation), or do we want them to do something more? Do we want them to be able to analyse (say, a problem), create (maybe a strategy) or evaluate options (like which of three alternative strategies is going to be the most effective)? Using a taxonomy to ask what we really want to develop in people allows a systematic approach that doesn’t rely as much on intuition and past experience. It also raises a comprehensive set of questions so we are less likely to overlook something.

Taxonomies also help us consider what pre-requisite knowledge and skills a person needs to be able to perform more complex types of work. For example, Bloom’s taxonomy prompts us to ask, what does a person have to know and comprehend to be able to analyse? What do they have to be able to analyse in order to evaluate? And, working from the revision of Bloom’s taxonomy, how do we get the worker learner to the highest and most complex layer of ‘create’? Whatever the end goal, taxonomies present us with a way to identify what the building blocks are for more sophisticated types of competence.

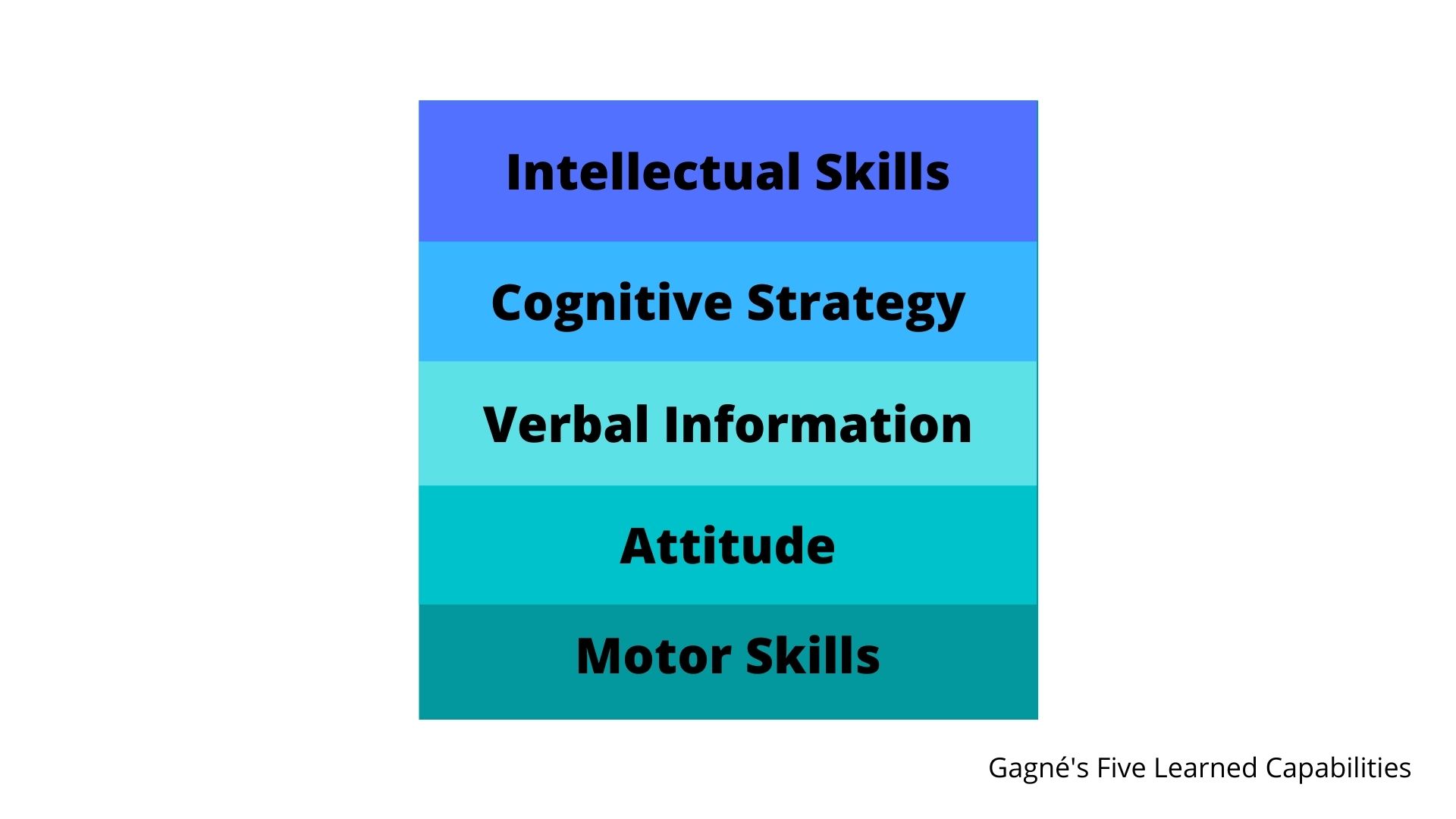

While Bloom’s taxonomy has been used extensively in education, the concept has been adapted for other fields. A more workplace-oriented taxonomy was created by Robert Gagné, which brought physical or ‘motor’ skills into the picture, along with attitudes.

This taxonomy is more action-oriented than Bloom’s which has made it a favourite of workforce development instructors. And because it brings in attitudes and motor skills, more of the range of important workplace learning features are included.

Finding and using a taxonomy to analyse learning needs is the first step in a systematic approach to workforce development. The second step is matching learning activities to your analysis. The full value of taxonomies emerges when they are complemented by teaching and training methods best suited to develop the kinds of learning set out in the taxonomy. A good example of a well-researched guide to matching your taxonomy analysis with learning activities is the article ‘Biology in Bloom’ by Alison Crow, Clarissa Dirks and Mary Wenderoth They offer an exhaustive list of learning activities aligned to the different levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. For example, practice in labelling diagrams promotes knowledge, describing a process in your own words develops comprehension, while comparing and contrasting different ideas develops analytic ability and giving learners the task of assessing each other’s work fosters evaluation.

As for Gagné’s taxonomy, researchers have helped identify what learning activities best support development of each type of learning shown in the taxonomy. Robert Gagné himself investigated this challenge in detail, and clarified ‘conditions of learning’ for each type. For example, he showed that attitude learning – a slower and more complex type to develop – can be supported by involvement of a respected colleague or admired person who can model the desired attitude. Gagné also explained how ‘direct reinforcement’ (rewards) and ‘vicarious reinforcement’ (seeing others rewarded) can help establish the desired attitude in employees. Other researchers have added to our understanding of how to develop attitudes, with role-play now considered a powerful way to shift attitudes.

Benjamin Bloom wrote, "we need to be much clearer about what we do and do not know so that we don't continually confuse the two." By following this two-step process – using a taxonomy and matching learning activities to the taxonomy – we can expect more direct results from our investment in people development. With a learning taxonomy, we can better understand the desired learning outcomes. Drawing on research into which learning activities match different parts of a taxonomy allows greater certainty about learning program design. If you are systematic about designing learning for workers the benefits for business – and workers too – can be enormous.

Dr Steven Hodge is President of the Australasian Vocational Education and Training Association (AVETRA) (avetra.org.au) and key contributor to debate in Australian post-compulsory education. His major analysis of policy in this space was recently published by the National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER) Steven is a member of the Griffith Institute for Educational Research (GIER) and of the School of Education and Professional Studies at Griffith University, where he is Director of the Master of Education and Graduate Certificate in Professional Learning programs.

Steven is Convenor of the Griffith Professional course - Strategic Learning Design

Advance your career with Griffith Professional

Griffith's new range of stackable professional courses designed to quickly upskill you for the future economy.

Professional Learning Hub

The above article is part of Griffith University’s Professional Learning Hub’s Thought Leadership series.

The Professional Learning Hub is Griffith University’s platform for professional learning. Our tailored professional learning focuses on the issues that are important to you and your team. Bringing together the expertise of Griffith University’s academics and research centres, our professional learning is designed to deliver creative solutions for the workplace of tomorrow. Whether you are looking for opportunities for yourself, or your team we have you covered.