Many years ago, I was serving on a gifted and talented education committee, at one particular meeting, one of the members had to leave early; a very eminent Professor in his field. He excused himself and made his way to the exit door, which led directly out to the street from the boardroom where we were meeting on this occasion.

The door was directly opposite where I sat at the other end of the table, so I had an easy view of comings and goings to the room. I observed as the Professor pushed hard at the unyielding exit door, endeavouring to make a hasty and non-disruptive departure from the in-progress meeting. He stopped momentarily, caught off guard by the immovable door, before trying again to push the unyielding door so he could leave. Another twice he strained, pushing at the door, to no avail. “It must be locked!” he exclaimed, feeling somewhat self-conscious having now tried three times to push the door open. By now other committee members seated closest to the door, had risen from their seats to go and assist the Professor. Before the helpers reached him, he let out an exclamation, “Oh, it says ‘Pull’!” Off he finally went, slightly embarrassed, pushing quickly though the exit door!

Who hasn’t done that?! We can all relate to pushing on a door that indisputably says ‘Pull’! Pushing, when we should have actually been pulling at an exit door! Yet, what struck me about this occurrence was the number of times he continually tried to push the door open. Failing the first time, yet not changing his actions to reach his goal, and persisting with the same action time and again, still without achieving the desired result of quietly exiting the meeting. At that first moment, coming to the incorrect conclusion that the fault lay with the ‘locked’ door! It made me think—no matter how eminent an expert a person may be in their field, it doesn’t mean they can see what’s right in front of them! Nor does it mean they will pivot to try different actions if their current action isn’t yielding the desired result! Persisting in the wrong direction might be perseverance, a sought-after trait for employees, but if it’s getting you more of what’s ineffective, it isn’t necessarily a successful characteristic.

Years later, I came across a very apt cartoon by Gary Larson “Midvale School for the Gifted”. Larson’s cartoon embodies the pushing when you should be pulling concept I had previously observed, in this instance it was clearly connected to gifted education with the words “Midvale School for the Gifted” visibly evident in the bottom right of his cartoon. Evidently, I’d observed a peculiarity of giftedness!

In the field of education, educators often find they are pushing when they need to be pulling; pushing the latest policy ‘initiative’ or endeavouring to cram the hottest politically-driven topic into an already overcrowded school curriculum. All the while knowing that they should be pulling for the needs of some of their students who are being neglected, one such population are our gifted and talented students.

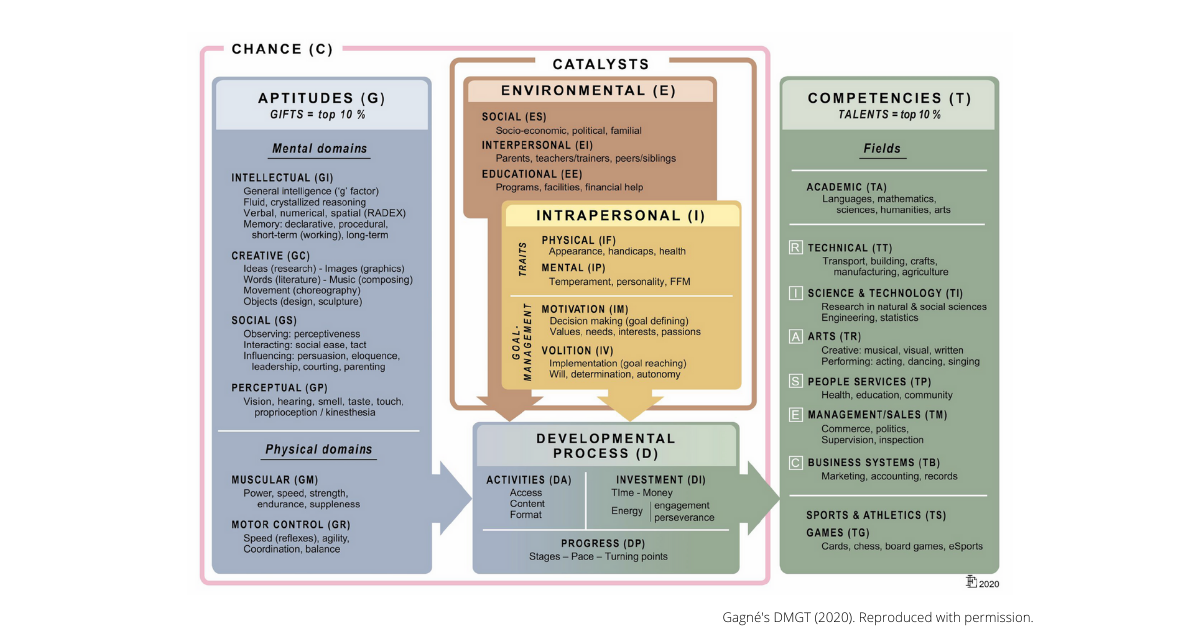

Despite international disagreement around definitions of giftedness, in Australia we mostly have a shared understanding of what giftedness is, and what talent is. This has been brought about by the adoption across the country of Canadian psychologist Françoys Gagné’s Differentiating Model of Giftedness and Talent (DMGT) (2020).

Let’s take a moment to briefly explore Gagné’s DMGT with a view to understanding some of the pushing and pulling around the educational needs of our gifted and talented learners, and how we may endeavour to engender success when they leave their schooling for the world of work.

On the left-hand side of Gagné’s model, there’s a list of six Aptitudes or Gifts under the first heading: Mental domains (e.g., Intellectual, Creative, Social & Perceptual), and the second heading: Physical domains (e.g., Muscular & Motor Control). In the centre of the model, is a short list of catalysts, consisting of Environmental catalysts (e.g., Educational) and Intrapersonal catalysts (e.g., Traits, such as persistence)—all leading through a complex talent developmental process involving Activities, Investment, and Progress, to actualize talent on the next part of the model.

On the right-hand side of the DMGT, we have Talents; these appear as Competencies in nine Fields of human endeavour—Academic; Technical; Science & Technology; Arts; People Services; Management/Sales; Business Systems; Sports & Athletics; and Games. It’s often assumed that gifted children will become talented individuals, pushed to university and onto a commensurate career trajectory. What often goes under-recognised is that many gifted individuals do not actualize their talent while engaged in the 13 years of formal schooling; despite the ‘pushing’ from some well-meaning adults. In actuality, the complex development process at the centre of Gagné’s model can take a lifetime to achieve (if ever).

We can see that both giftedness and talent can occur in many areas, however, they don’t always get recognised at school. Likewise, not all the talent competencies can be directly connected with what is taught and assessed in schools. Some gifted students leave school never having been recognised as either gifted or talented by the narrowly focused assessments of academic-based talents synonymous with educational systems the world over. Scott Barry Kaufman personifies this in his seminal book Ungifted Intelligence Redefined: The truth about talent, practice, creativity, and the many paths to greatness. Kaufman elucidates about how interpretation of traditional metrics of intelligence are erroneous, revealing that there are many and varied pathways to eminence; it’s definitely not just children recognised through high academic performance in school that can go on to have successful careers.

In the workplace, gifted and talented individuals can be innovators, visionaries, creators and problem solvers who can get to the crux of complex issues. Sternberg says these characteristics are synonymous with practical giftedness, one of the most important, yet, fairly overlooked kinds of giftedness. Practical giftedness is focused on the more practical abilities needed for real-world success and is different from academic school-recognised giftedness and talent; it is said to be the adaption to the everyday world, the ability to recognised when to push, when to pull and, when to pivot.

Some of the characteristics of those with practical giftedness are the ability to adapt to, and shape their environments, acquiring knowledge from experiences, and then recognising when and how to apply this knowledge to solving complex real-world problems. Practical giftedness is about recognising everyday situational skills and knowledge and applying these in practical but innovative ways; quite distinct from the one-right answer traditional academic-based problem solving synonymous with schooling.

Unfortunately, many individuals with practical giftedness leave school frequently thinking they aren’t gifted or talented at all. For some gifted students, their giftedness goes unrecognised in school and their needs remain unmet. Maybe some of these unrecognised individuals achieved averagely at school, with the narrow-focused end-of-school assessments clearly never recognising their creative or critical thinking and experiential problem-solving abilities. As Don Wettrick aptly put it, “We do our students a disservice when we… fail to empower them with the skills and abilities they will need to navigate rough and shifting seas. We don’t need students who can fill in bubbles on a multiple-choice test; we need students who can create, innovate, connect, and collaborate. We need students who can identify and solve complex, real-world problems. Changing the way we educate [and assess] students is not only necessary…it’s a moral imperative.”

There are many examples of individuals who left school early, either to pursue careers not espoused by schooling systems or because their talent was unrecognised at school. Take for example, ‘Time Magazine’s “Man of the [20th] Century”, Albert Einstein, he was not an ‘Einstein genius’ in school; in fact, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist dropped out of high school. And the list goes on… David Karp dropped out of an elite science high school and ultimately developed Tumblr, the microblogging and social networking website. Actor Hilary Swank dropped out of high school yet, went on to have a highly successful acting career. What all these individuals have in common is their eminence in their fields, their talent; pushing themselves to greatness, but recognising when to pivot and adapt, to pull instead of push.

Exceptional intellectual and creative talents can lead to highly successful careers. Future employment opportunities will require various degrees of proficiency in a multitude of areas of talent development—high-level analytical thinking skills, problem-solving skills, ‘learning how to learn skills’ in new and evolving technologies, and creativity skills; Sternberg’s practical giftedness.

Until education systems recognise that gifted students are remaining unidentified and unsupported at school due to their narrow focus on academic talent, individuals will continue to leave school early. In some instances, gifted students may be able to create their own work opportunities; charting their own paths as innovators, recognising when and how they should push or pull, or pivot. Ultimately, there needs to be a definitive focus on educating gifted students for all of life, to address the uncertainty of what jobs and careers may be available in the future.

Want to learn more?

Are you a teacher? Want to better understand the complexities and nuances of gifted or talented learners in your classroom? Dr Michelle Ronksley-Pavia has developed an online, self-paced course that is ready to help. Click here to get started.

Dr Michelle Ronksley-Pavia is a lecturer in Professional Experience and Special and Inclusive Education in the School of Education and Professional Studies, Griffith University. Dr Ronksley-Pavia is also a member of Griffith’s Institute for Educational Research, and a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. As a leading international expert in the field of gifted and talented education Dr Ronksley-Pavia has a wealth of experience supporting and advocating for the needs of gifted and twice exceptional learners and their families. Dr Ronksley-Pavia's expertise as a leader in the field of twice-exceptional research and advocacy has been recognised by the Bridges 2e Center for Research and Professional Development.

Dr Michelle Ronksley-Pavia is a lecturer in Professional Experience and Special and Inclusive Education in the School of Education and Professional Studies, Griffith University. Dr Ronksley-Pavia is also a member of Griffith’s Institute for Educational Research, and a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. As a leading international expert in the field of gifted and talented education Dr Ronksley-Pavia has a wealth of experience supporting and advocating for the needs of gifted and twice exceptional learners and their families. Dr Ronksley-Pavia's expertise as a leader in the field of twice-exceptional research and advocacy has been recognised by the Bridges 2e Center for Research and Professional Development.

Visit Michelle's Griffith Experts page here

Professional Learning Hub

The above article is part of Griffith University’s Professional Learning Hub’s Thought Leadership series.

The Professional Learning Hub is Griffith University’s platform for professional learning and executive education. Our tailored professional learning focuses on the issues that are important to you and your team. Bringing together the expertise of Griffith University’s academics and research centres, our professional learning is designed to deliver creative solutions for the workplace of tomorrow. Whether you are looking for opportunities for yourself, or your team we have you covered.

Advance your career with Griffith Professional

Griffith's new range of stackable professional courses designed to quickly upskill you for the future economy.