As the world comes to grips with the far-reaching impacts of COVID-19, the need for creative solutions to challenges facing our health, our work, our communities and economies is greater than ever.

Recognising this, late last year partners of the Culture 2030 Goal Campaign released a statement on culture and the COVID pandemic calling on United Nations (UN) agencies, governments and all other stakeholders to put culture at the heart of their response to the pandemic. Specifically, the campaign urges us to recognise, incorporate, and support cultural concerns in our response to the growing inequalities exacerbated by the pandemic, rising mistrust in policy systems, violence against vulnerable groups, military conflicts, and the climate emergency (Culture and the COVID-19 Pandemic).

During lockdowns across the world, music and cultural activities have played a crucial role in bringing inspiration, comfort, connection, and hope to people’s lives. Musicians, and a myriad of workplaces across sectors (including cultural organisations, NGOs, educational institutions, and government departments), have increasingly harnessed music’s capacity for addressing some of our most complex social challenges in the wake of the pandemic and its associated restrictions.

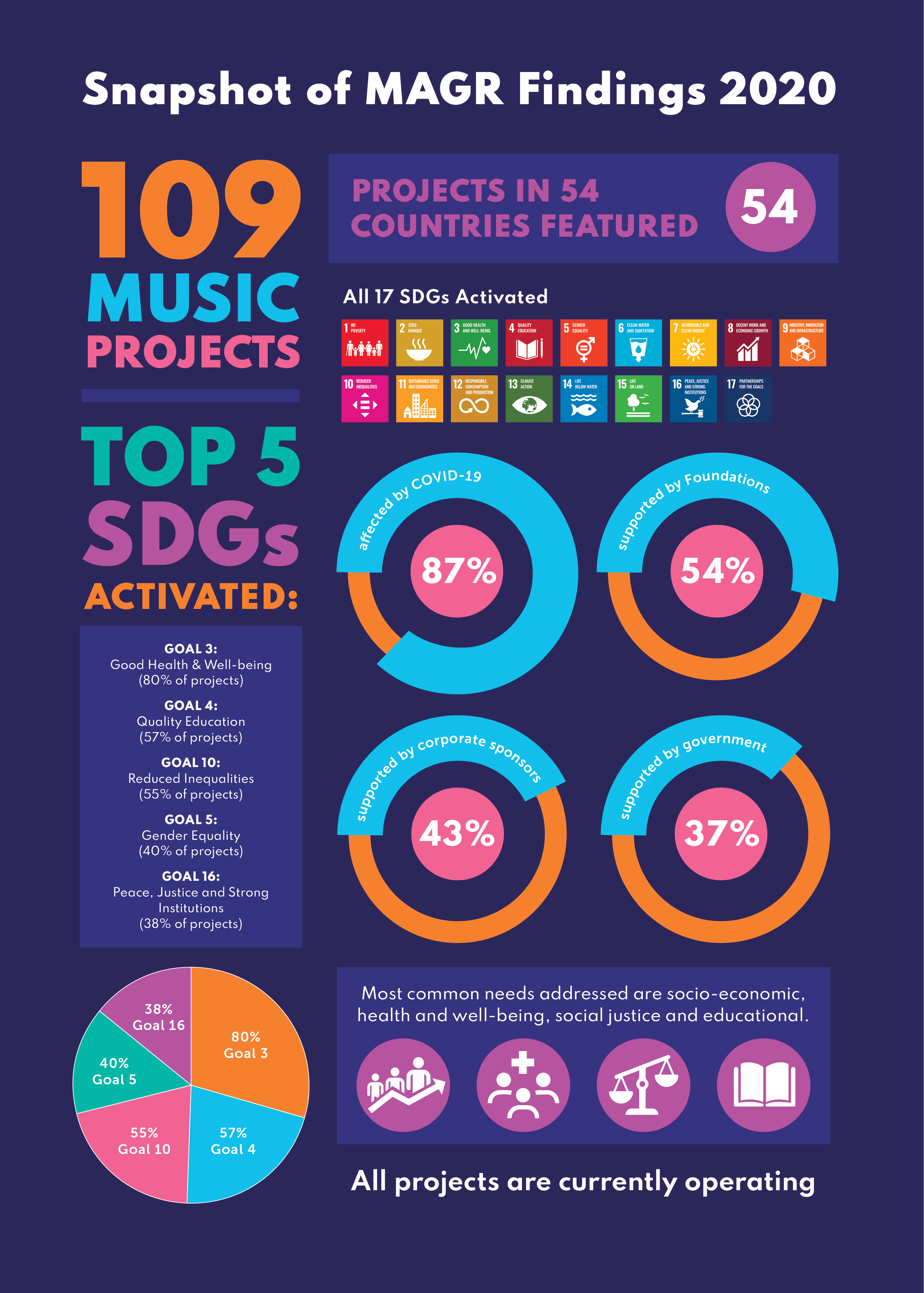

To document this work on a global scale Professor Barbara Hesser (New York University) and I released the 5th edition of Music as a Global Resource Compendium, in honour of the UN’s 75th Anniversary and in response to the global pandemic. Featuring 109 music projects from 54 countries, it demonstrates how music projects are addressing pressing cultural, social, health, educational, environmental, and economic issues, and collectively advancing all 17 of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Here is a snapshot of the findings.

How can music help advance the SDGs?

Musicians have the unique capacity to help address some of the most pressing issues facing our generation. They can activate the social imagination and bring forth new ways of knowing, understanding and making sense of an increasingly complex world. This is because music has a unique capacity to communicate beyond the limits of language, and express difficult ideas in ways that evocatively open hearts and minds. In other words, music is not merely about life, but is rather implicated in the formulation of life. It is always in flux, changing in response to the world and in turn changing the world (to view a public talk I gave on this topic click here).

Music never operates in isolation. As the projects in our compendium show, music accumulates its meaning and identity from the ways in which it participates in other activities. While music is never a magic bullet, it can be a crucial piece in the puzzle when addressing some of the most pressing challenges facing our generation, and an important cultural solution that can help advance the SDGs.

Music has the capacity to advance the SDGs across a wide range of domains from the individual to the interpersonal, and upstream to the community and structural levels. That said, when thinking about music and the SDGs, music also needs to be understood as a creative and cultural activity that has both intrinsic and instrumental (e.g. social) value. People are not customarily drawn to participating in the music projects featured in our compendium for their instrumental benefits alone (for example their SDG outcomes), but rather they engage because music can provide them with meaning and a distinctive type of pleasure and emotional stimulation. These intrinsic effects are satisfying in themselves; however, many of them can lead to individual capabilities and social outcomes that do have compelling instrumental benefits in relation to the SDGs. Here are some examples.

Celebration Choir in Aotearoa, New Zealand

The music therapist-led community singing group, the Celebration Choir in Aotearoa, New Zealand, offers choral singing therapy for adults living with acquired neurological conditions, such as stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and dementia, and has continued to operate online during lockdowns, reducing the social isolation and enhancing the health-related quality of life of its elderly participants.

Afghanistan National Institute of Music

Founded in 2010, Afghanistan National Institute of Music (ANIM) is Afghanistan’s first and only institute of music where talented Afghan children, regardless of their gender, social circumstances, and ethnic background, are trained in a co-educational environment in Afghan traditional and Western classical music, in an effort to promote child and human rights, musical rights, integrated learning environments, and cultural dialogue and diplomacy.

Musicians for Human Rights in Italy, Greece and Switzerland

This NGO (Musicians for Human Rights) encourages professional musicians, audiences, and students to take action to advance the well-being of people living at the margins through its flagship ensemble, the Human Rights Orchestra, human rights programs in schools, and social music projects in refugee camps, detention centres, and community centres across Europe.

Leweton Cultural Experience in Vanuatu

The Leweton Cultural Experience uses traditional forms of storytelling such as music, dance, arts, language, and cultural practices (for example the Women’s Magical Water Music ceremony), to promote cultural sustainability, environmental knowledge around climate change, as well as vital income generation through cultural tourism.

Musicians Without Borders in El Salvador, Kosovo, Netherlands, Palestine, Rwanda

Musicians Without Borders is the world’s pioneer NGO using music for peacebuilding and social change. They work in partnership with local musicians and organisations to use the power of music to bridge divides, connect communities, and heal the wounds of war through trauma-informed ways of facilitating music making.

These examples show how music making can play a key role in ‘translating’ the universal language of the SDGs into the individual and collective lives of citizens in specific communities, cities, and regions. This is a process the Culture 2030 Goal Campaign terms ‘cultural localisation’ of the SDGs. As these examples demonstrate, musicians and culture-bearers play a central role in capturing the public’s imagination and making these SDGs more locally desirable, relevant, and effective.

What’s next?

These compelling examples, and many others from across the world, have prompted renewed calls for music, and culture, to play a key role in the SDGs Implementation Decade (2020-2030). This does prompt us to ask how we can best champion these efforts in our local contexts, whether we work in music or any other profession.

Alex Hannant and Ingrid Burkett’s recent Thought Leadership piece on the SDGs provides a clue. They argue for mission-led approaches to conceptualising and orchestrating movements for intentional, systemic and structural change. As they outline, addressing the SDGs in this way requires innovation and genuine cooperation across diverse industries, sectors, geographies and groups.

Surprisingly, to date, music and the broader arts sectors have rarely been integrated into the backbone of these kinds of cross-sector, mission-led efforts aimed at addressing the SDGs. This is particularly striking considering the mounting evidence base that documents the cultural, social, emotional, physiological, cognitive, and economic benefits that can come from participating in music. This may be due in part to a reluctance from intrinsically-motivated musicians to play into these larger efforts and social policy imperatives, or it may be due to the fact that we need to understand more deeply how music can most effectively flow upstream to influence systemic social change.

Given the compelling examples of music initiatives the world over, and the ubiquitous role that music plays in all our lives at home, at work, and in our communities, there is a compelling case to be made for integrating a more ‘creative turn’ in our collective, mission-led approaches to addressing the SDGs. Music and music initiatives have the potential to provide exactly the kind of experimental, creative, out-of-the-box approaches that are needed to drive these collective efforts.

If you are inspired to think further about how your organisation can take a mission-led approach to addressing the SDGs, it would certainly be worth imagining how music, creativity, and culture could ignite, amplify, deepen, and unlock new ways of enacting your work in this space.

Want to find out more

To inspire your thinking on how music, and culture more broadly, can contribute to this agenda, you might like to visit the Culture2030 Goal Campaign.

Click here to download the Music as a Global Resource Compendium for free.

You might also be interested in watching the Fair Saturday Forum resources, which bring together international cultural and social leaders to discuss how culture and social innovation can build more humane and positive societies.

Reference

.

Brydie-Leigh Bartleet is an Australian Research Council Future Fellow and Professor at the Queensland Conservatorium Research Centre, Creative Arts Research Institute, Griffith University (Australia). She is one of the world’s leading community music scholars whose research has advanced our understanding of the cultural, social, economic, and educational benefits of music and the arts in First Nations’ Communities, prisons, war affected cities, educational and industry contexts. She is the President of the Social Impact of Music Making (SIMM) international research platform (2021-2024) and Associate Editor of the International Journal of Community Music. She has served as Director of the Queensland Conservatorium Research Centre (2015-2021) and Deputy Director (Research) of the Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University (2016-2021), as well as the Board of Music Australia (2013-2021), and as Chairperson and Commissioner of the International Society for Music Education’s Community Music Activities Commission (2010-2016). In 2014 she was awarded the Australian University Teacher of the Year, and in 2022 she will be a Fulbright Scholar at New York University Steinhardt (awarded 2020).

Professional Learning Hub

The above article is part of Griffith University’s Professional Learning Hub’s Thought Leadership series.

The Professional Learning Hub is Griffith University’s platform for professional learning and executive education. Our tailored professional learning focuses on the issues that are important to you and your team. Bringing together the expertise of Griffith University’s academics and research centres, our professional learning is designed to deliver creative solutions for the workplace of tomorrow. Whether you are looking for opportunities for yourself, or your team we have you covered.

Advance your career with Griffith Professional

Griffith's new range of stackable professional courses designed to quickly upskill you for the future economy.